Ethereum’s switch to proof-of-stake is scheduled for mid-September. What are the possible risks? How does it work compared to Bitcoin’s proof-of-work consensus?

The below is a full free article from a recent edition of Bitcoin Magazine Pro, Bitcoin Magazine’s premium markets newsletter. To be among the first to receive these insights and other on-chain bitcoin market analysis straight to your inbox, subscribe now.

The Merge

On September 15, Ethereum is planning to undergo its long-promised “Merge,” where the protocol will shift from a PoW (proof-of-work) consensus mechanism to a PoS (proof-of-stake) consensus mechanism.

In this report, we will provide details on how the proof-of-stake mechanism works for Ethereum, using technical definitions provided from Ethereum documents. Second, we will evaluate the move to proof-of-stake from first principles, which will include an explanation as to why much of the reasoning for the move is possibly flawed. Last, we will cover the risk factors of the Ethereum PoS mechanism comparing and contrasting the governance to Bitcoin and a PoW consensus mechanism to articulate the fundamental differences between the systems.

This piece was partially inspired by Glassnode’s Lead Analyst, Checkmate’s latest work on Why The Ethereum Merge is a Monumental Blunder.

The Basics

With the shift in consensus mechanisms, Ethereum shifts its block production away from GPU (graphics processing unit) miners over to staking validators.

Validators: “To participate as a validator, a user must deposit 32 ETH into the deposit contract and run three separate pieces of software: an execution client, a consensus client, and a validator. On depositing their ether, the user joins an activation queue that limits the rate of new validators joining the network. Once activated, validators receive new blocks from peers on the Ethereum network. The transactions delivered in the block are re-executed, and the block signature is checked to ensure the block is valid. The validator then sends a vote (called an attestation) in favor of that block across the network.” – Ethereum.org

Validators take the role of block production away from miners, and importantly, transfer the power structure away from real world energy input (in the form of hashes) towards capital, in the form of staked ether.

Security: “The threat of a 51% attack still exists on proof-of-stake as it does on proof-of-work, but it’s even riskier for the attackers. An attacker would need 51% of the staked ETH (about $15,000,000,000 USD). They could then use their own attestations to ensure their preferred fork was the one with the most accumulated attestations. The ‘weight’ of accumulated attestations is what consensus clients use to determine the correct chain, so this attacker would be able to make their fork the canonical one. However, a strength of proof-of-stake over proof-of-work is that the community has flexibility in mounting a counter-attack. For example, the honest validators could decide to keep building on the minority chain and ignore the attacker’s fork while encouraging apps, exchanges, and pools to do the same. They could also decide to forcibly remove the attacker from the network and destroy their staked ether. These are strong economic defenses against a 51% attack.” – Ethereum.org

The Ethereum website claims that the security will be stronger in a PoS consensus system rather than a PoW consensus system, but we consider this to be highly controversial.

While a proof-of-work protocol relies purely on economic incentives and real world physical constraints to secure the chain against attackers in the form of an attack, PoS relies on “social governance” through slashing to attempt to keep stakers honest. To clarify further, to 51% attack the Bitcoin network (to execute a double spend), an attacker would need access to an immense amount of physical infrastructure and energy resources in the form of ASIC miners, electrical infrastructure, and (cheap) energy, before an attack is even attempted. To cap it all off, any hypothetical attacker that does gain access to these things will quickly realize it is more economical to simply be an honest miner.

With proof-of-stake, stakers are kept honest through slashing, where hostile peers see their ether get destroyed (for actions such as proposing multiple blocks in the same slot or violating consensus). Similarly, in the case of potential censorship by a dominant majority of stakers (more on this later), there is an option for a minority soft fork. To quote Vitalik Buterin,

“For other, harder-to-detect attacks (notably, a 51% coalition censoring everyone else), the community can coordinate on a minority user-activated soft fork (UASF) in which the attacker’s funds are once again largely destroyed (in Ethereum, this is done via the “inactivity leak mechanism”). No explicit “hard fork to delete coins” is required; with the exception of the requirement to coordinate on the UASF to select a minority block, everything else is automated and simply following the execution of the protocol rules.”

Miner Extractable Value (MEV)

MEV is an abbreviation of “Miner Extractable Value” that has recently changed to “Maximal Extractable Value” which refers to the profits that can be made by extracting value from Ethereum users through block production.

Given the vast financial application ecosystem built on Ethereum, there is often an arbitrage opportunity in the ordering of transactions. The producers of blocks can reorder, sandwich (the act of front-running a large order, only to use their market order as exit liquidity to profit from the spread), or censor transactions within blocks being produced. It typically affects DeFi users interacting with automated market makers and other apps.

Treasury Sanctions And The Looming Threat Of OFAC Regulations

Last week, the U.S. Treasury announced that Tornado Cash was added to the U.S. OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control) SDN list (the list of specially designated nationals with whom Americans and American businesses are not allowed to transact). The sanctions placed on Tornado Cash were particularly notable because they were placed not on an individual person or particular digital wallet address, but rather the use of a smart contract protocol, which in the most basic form is just information. The precedent set by these actions are not ideal for open-source software development.

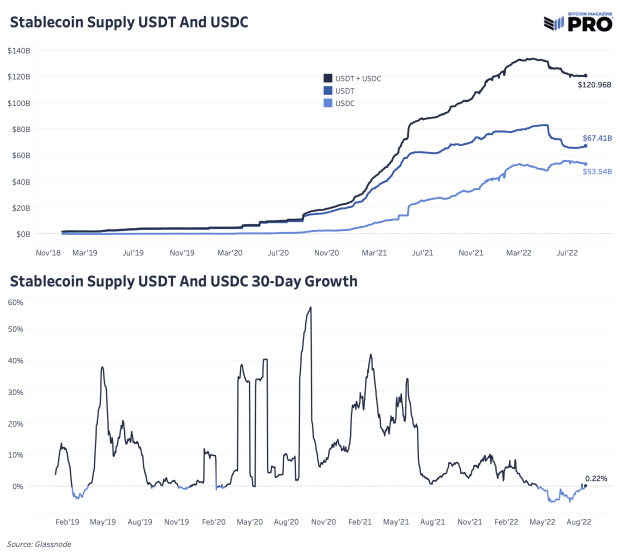

Regardless of the legal and constitutional precedent of the move, the response from stakeholders across the Ethereum and DeFi ecosystems was the biggest eyeopener. Merely hours after the Treasury added Tornado Cash to the SDN list, Circle, issuer of $53.5 billion stablecoin USDC, had updated its blacklist to include every sanctioned address and smart contract, officially disbanding holders of USDC from interacting with the protocol, and even seizing a small amount of funds.

Circle released the following statement following the move,

“Circle is a regulated company that created, and now manages and issues one of the largest dollar digital currencies in the world. As such, we conform with sanctions and compliance requirements, and have done so for years, because building a faster, safer, and more efficient way to move value globally requires trust, and because it’s the law. That trust has helped USD Coin (USDC) grow tremendously in the last few years and has established USDC across the digital asset economy globally.” – Circle blog

This set off a chain reaction in the DeFi ecosystem, where much of the infrastructure that had been built on top of / around USDC, while it had now become increasingly obvious that this wasn’t a sustainable long-term solution for supposedly decentralized finance. MakerDAO

In particular, there began to be an increasing amount of worry about DeFi protocol MakerDAO, which leverages the Ethereum blockchain to create an over-collateralized soft-pegged stablecoin using blockchain-based collateral.

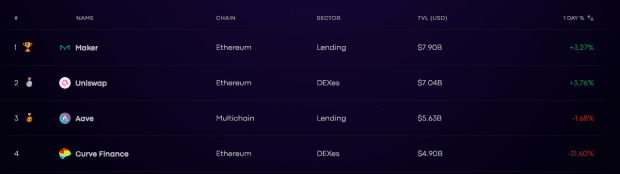

Despite the many flaws of using TVL (total value locked) as a measure, Maker’s place atop the list for DeFi protocols is telling. Within an ecosystem that saw explosive growth post 2020, Maker’s rise was among the most meteoric.

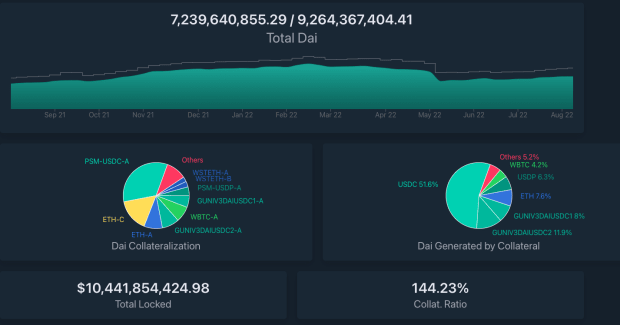

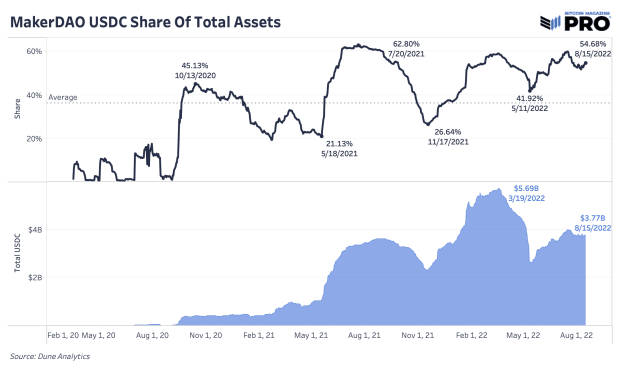

MakerDAO allows users to generate DAI (an algorithmic stablecoin) by depositing collateral assets into Maker Vaults, which has become increasingly reliant on USDC.

At the time of writing, Maker has approximately $10.44 billion in assets locked in its vaults, with $7.23 billion of DAI issued against that collateral.

Shown below is the percentage of MakerDAOs collateral that is USDC along with the aggregate USDC value in the pane below:

It is problematic when the foundation of a so-called decentralized financial revolution is so reliant on collateral that’s the liability of a central issuer.

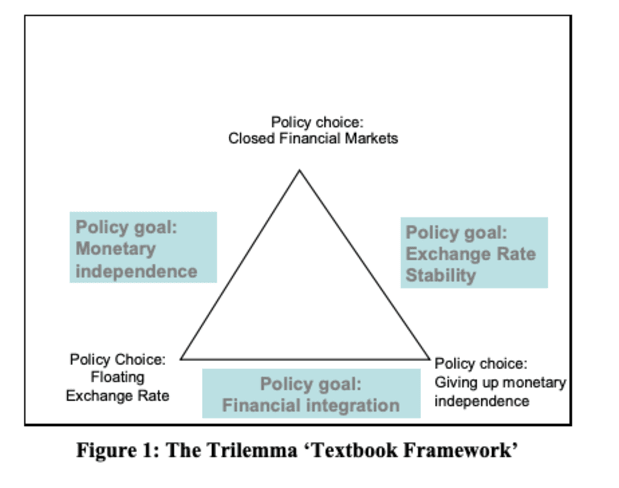

However, you can’t really blame Maker for its reliance on USDC. They are attempting to solve an economic problem that has existed for centuries. As a result of attempting to peg DAI to $1, the architects of MakerDAO faced the classic currency peg trilemma. Economic history has shown that it is only possible to achieve two of three desired policy outcomes at one time:

- Setting a fixed currency exchange rate

- Allowing capital to flow freely with no fixed currency exchange rate agreement

- Autonomous monetary policy

In the case of DAI, MakerDAO’s algorithmic stablecoin, the options are similar, but the recent Treasury sanctions and subsequent compliance on behalf of Circle has led MakerDAO to question its increasing reliance on USDC:

The trilemma in Maker’s case is the following:

- Maintain USD peg

- Abandon stablecoins as collateral

- Scale MakerDAO

Maker can only choose two of the three options.

With the recent developments with USDC, it seems like Maker is considering the latter two, with the consequence being the abandonment of the USD peg for DAI. With this decision, the idea was floated to convert all USDC into ETH, given the bearer asset nature of the cryptocurrency asset relative to the tokenized liability of Circle, a centralized institution regulated by the U.S. government.

This led to a response from Vitalik Buterin, which highlighted the risks of backing an algorithmic stablecoin with volatility collateral (albeit overcollateralized as it currently stands).

This is a large problem for the DeFi space in general. How do you build a decentralized ecosystem of borrowing/lending, when the very thing that is in the most demand to be borrowed is a permissioned “off-chain” asset (the U.S. dollar)? Algorithmic stablecoins are possible, but require over-collateralization and leave users prone to the risk of margin calls/liquidation if the price of the pledged collateral drops.

The increasingly realized threat of censorship and regulations coming through the pipe means that DeFi as it is known today, with large reliance on centralized stablecoins as collateral, is vulnerable.

To quote Lyn Alden,

“Stablecoins are useful, but centralized. And by extension, they centralize any network that is overly reliant on them.”

Additional Infrastructure Censorship

Shortly after the Treasury announcement and blacklists from Circle, key Ethereum infrastructure project Infura, which allows for users/apps to connect to the Ethereum blockchain, began to block RPC (remote procedure call) requests to Tornado Cash. Infura is the service provider for the most-used wallet application in Ethereum, MetaMask, among other applications. Infura is the largest node provider in the Ethereum ecosystem, and even though advanced users route around the ban using their own clients, the marginal user is simply not at that level of technical competency.

Following the Tornado Cash incident, founder and CEO of Coinbase Brian Armstrong spoke out about the sanctions from the U.S. Treasury, citing the bad precedent that comes with sanctioning a technology rather than a direct individual or entity. He followed the criticism by stating,

The Centralization Problem With PoS Ethereum

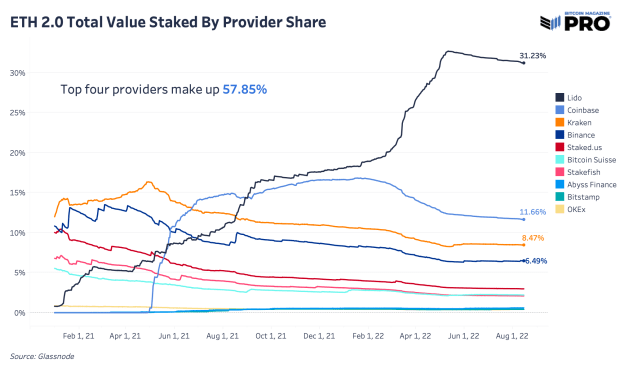

While Ethereum proponents and developers will claim that the switch to PoS makes Ethereum much more decentralized and resistant to hostile attack, the empirical evidence points to an increasing amount of staking centralization, which can lead to some large problems. At the time of writing, 57.85% of ether is being staked with four providers, with Lido holding by far the largest market share.

Lido is a liquid staking solution which allows users to stake their ether (and forgo the 32 ETH threshold for smaller holders) in exchange for stETH token, which is a claim that can be redeemable for ether at some point in the future.

By design, current stakers of ether cannot unstake their coins, even directly after the Merge takes place, with Ethereum roadmap estimates suggesting the possible enabling of withdrawals from staking validators at some point in 2023.

The full code enabling withdrawals post-Merge has not yet been completed.

Given that the withdrawals to unstake ETH is not yet an option for users, a liquid staking solution such as Lido (which is far and away the market leader) is an extremely attractive option for users who wish to have access to their coins to trade/hedge/collateralize their ETH.

In a previous issue of ours, Celsius and stETH – A Lesson on (il)Liquidity, we wrote about the one-way dynamic of stETH redeemability:

“stETH is a token issued by Lido which provides users a service where they are able to lock any amount of ETH in exchange for the stETH token, which can be rehypothecated in DeFi to earn yield, serve as collateral, etc. This contrasts to other forms of ETH staking where your assets are not liquid.” – Celsius and stETH – A Lesson on (il)Liquidity.

(Liquid) Staking looks to be a winner-take-all (or most) dynamic, where users choose the service that has the smoothest user experience, the most liquid secondary market (ETH to stETH is currently a one-way market until PoS withdrawals are enable, but users can swap in the secondary market), and the most attractive fee revenue (more on this later). These are just some of the reasons that Lido’s proof-of-stake market share is as large as it is.

The Growing Risks Of Lido

In a blog post written on Ethereum.org by Danny Ryan, a lead researcher for the proof-of-stake rollout for the Ethereum Foundation, Ryan highlighted the increasing risks that centralization of stake in Lido could lead to for Ethereum:

“Liquid staking derivatives (LSD) such as Lido and similar protocols are a stratum for cartelization and induce significant risks to the Ethereum protocol and to the associated pooled capital when exceeding critical consensus thresholds. Capital allocators should be aware of the risks on their capital and allocate to alternative protocols. LSD protocols should self-limit to avoid centralization and protocol risk that can ultimately destroy their product.

“In the extreme, if an LSD protocol exceeds critical consensus thresholds such as 1/3, 1/2, and 2/3, the staking derivative can achieve outsized profits compared to non-pooled capital due to coordinated MEV extraction, block-timing manipulation, and/or censorship – the cartelization of block space. And in this scenario, staked capital becomes discouraged from staking elsewhere due to outsized cartel rewards, self reinforcing the cartel’s hold on staking.”

In Ryan’s words, risks exist if a staking solution grows to hold a critical amount of stake in a PoS system, due to the ability to use coordinated MEV (miner extractable value), and/or the ability to censor certain actors/transactions at a whim.

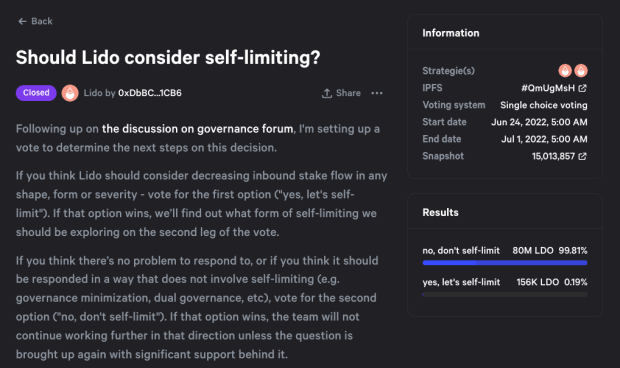

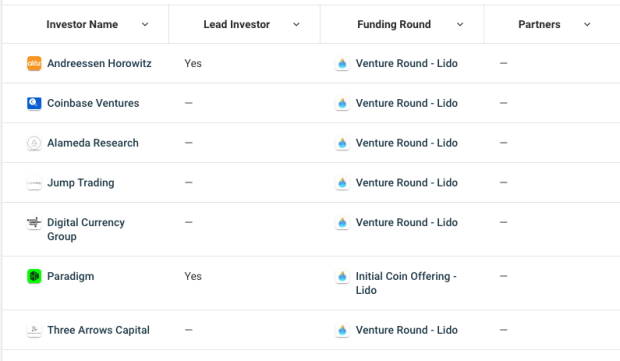

Ryan’s suggestion, to have the liquid staking protocol self-limit to avoid centralization and protocol risk, was put up to vote by Lido via the governance token LDO.

Votes conducted with the LDO governance token is how key Lido decisions are made.

A vote for LDO holders was taken to self-limit the staking share for Lido, with the poll starting on June 24 and concluding on July 1. The vote was conducted on Snapshot, a popular tool for DAOs (decentralized autonomous organizations) on Ethereum to conduct protocol voting/governance.

The results?

A 99% landslide for choosing to not self-limit by LDO holders.

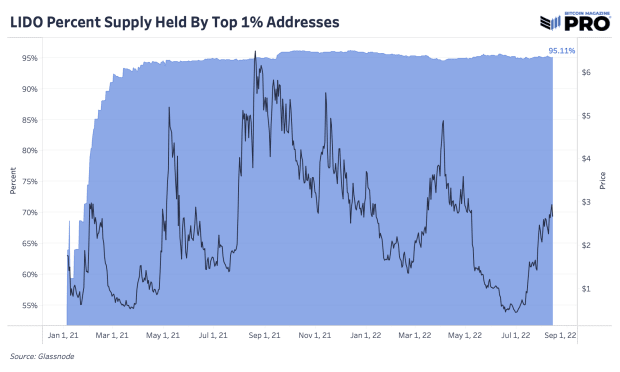

The landslide vote shouldn’t come as a surprise, given that 95.11% of LDO tokens are held within the top 1% of addresses, most of which are U.S.-regulated venture capitalist (VC) firms.

Given that Lido governance is indirectly controlled by major venture capitalist firms, of which most operate under U.S. jurisdictions, ETH has a growing centralization problem.

When summing up the amount of staked ETH across Lido, Coinbase, Kraken, and Staked alone, 56.57% of staked ETH currently resides in service providers directly or indirectly under the jurisdiction of the U.S. government.

Circling back to the Merge as a consensus change, do you remember the key change that Ethereum is undertaking to go from a proof-of-work to a proof-of-stake network?

Block production is moving from a service conducted by miners to validators.

This means that validators, those who are staking 32 ETH, are the ones in charge of the block production of the Ethereum network. The risk for Ethereum as well as the centralized service providers, is that pressure from U.S. authorities to censor at the protocol level. Referring back to Buterin’s post, the Ethereum community in response to censorship from centralized entities would soft fork, to delete the “attacker’s” stake:

“For other, harder-to-detect attacks (notably, a 51% coalition censoring everyone else), the community can coordinate on a minority user-activated soft fork (UASF) in which the attacker’s funds are once again largely destroyed (in Ethereum, this is done via the “inactivity leak mechanism”). No explicit “hard fork to delete coins” is required; with the exception of the requirement to coordinate on the UASF to select a minority block, everything else is automated and simply following the execution of the protocol rules.”

The problem with this strategy is that due to the large DeFi/L2 ecosystem built around Ethereum over the years, any dissident fork (rebelling against OFAC compliance) would likely lose its ecosystems of stablecoins and trusted oracles.

Fork Ethereum without the backing of USDC, and a daisy chain of DeFi liquidations begins as the non-compliant fork now has USDC-forked tokens that are intrinsically worthless, sparking a massive contagion effect / margin call scenario.

Bitcoin underwent a similar test in 2017 with the fork wars, where a massive push was made by representatives from over 50 companies attending a meeting, notoriously referred to as the New York Agreement, to expand the block size of Bitcoin, which was a required change in consensus.

Individual users of bitcoin revolted against such changes, given the precedent that coordinated hard forks and changing consensus rules would have, and instead implemented a soft fork that enabled the later build-out of scaling solutions such as the Lighting Network. The key difference between the fork proposed by the New York Agreement conspirators and the ones activated by a large number of average bitcoin users was that the former was a proposal to hard fork, while the latter was an opt-in soft fork, meaning that consensus is still backwards-compatible for nodes that did not upgrade.

In Ethereum’s case today, the increasing encroachment of possible future censorship at the block production level would not require another fork, other than the one that is already planned for the Merge today. The fork would be on the dissident users, who are pushing for an open, censorship-resistant future.

The distinct difference between what Bitcoin accomplished in 2017 versus what Ethereum may very well face in the future is that a large portion of its ecosystem would likely be lost along the way given the dependence on centralized stablecoins such as USDC in its DeFi ecosystem.

PoS Slashing Hypothetical

Let’s list a simple hypothetical and see how it may play out. The U.S. government imposes increased regulations on Circle, the USDC issuser. They propose to limit transactions from a list of associated Ethereum addresses. Centralized U.S. companies that are Ethereum staking validators must adhere to these regulations by rejecting blocks with these transactions or blacklisting addresses. If they do not, they will face increased scrutiny, fines, sanctions, etc.

The proposed Ethereum solution is slashing by consensus. Slashing would destroy a percentage of the validator’s ETH stake forcing them to reconsider their bad censorship actions. Yet, consensus needs to come from a majority of nodes while the majority of staked ETH already sits with these centralized validators (and cannot be withdrawn as of now).

By not having more solo validators and nodes, consensus would exist with these larger centralized groups and not with the majority of ETH users. In the scenario, centralized groups wouldn’t have the incentive to bravely fight against government regulations. While users, who have staked their ETH with these centralized institutions, would not have the incentive to want to slash their own ETH holdings in the name of censorship resistance.

Other ETH users and nodes can push against this to force a potential minority fork or UASF (user-activated soft fork). However this would likely come at the expense of losing Circle and much of the developed DeFi infrastructure that has been built on Ethereum over the last few years.

In an adversarial scenario, given the precedent set by Circle last week, is there a legitimate case to be made for Circle not choosing the OFAC-compliant chain/fork?

We should be clear that we unequivocally do not support the sanctioning of smart contracts, base-level censorship, or imposed top-down state control over the mediums of communication or economic value.

All we are aiming to do is pose what we view are legitimate questions. Bitcoin, Ethereum, and broadly the cryptocurrency market at large are attempting to take the issuance and control of money away from the state.

History shows that there will be a vested interest in controlling/co-opting this endeavor.

Never-Ending Forks

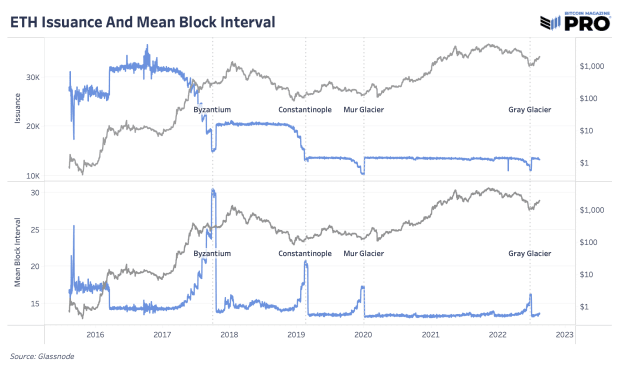

Throughout Ethereum’s history, there’s been a number of substantial hard forks and updates by design to create an ever-evolving protocol. Many of these changes have included changes to difficulty bombs to push back potential Merge dates and altering supply issuance over time to be increasingly disinflationary. Proponents of Ethereum argue this makes ether “ultra-sound” money, which is paradoxical given that the soundness of money is derived from the inability to be changed/altered/diluted in any way, especially for political purposes.

Hard forks and major updates at the core of Ethereum’s strategy is almost the exact opposite of Bitcoin’s. Updates and changes to the consensus protocol have changed as the narratives and vision of what Ethereum should be has changed. While this may be attractive for its idealist users/proponents, this leaves Ethereum’s governance to be subject to later politics.

With the rising uncertainty and risks of life post the PoS Merge, all we can expect is for hard forks and major updates to continue. For many, this is attractive as the Ethereum community will work to build new solutions and complex protocol designs depending on what major challenge they face. Yet for others, Ethereum as an asset and protocol look like an engineering experiment that is lacking true stability.

10/16/2017: Byzantium update, “A hard fork is a change to the underlying Ethereum protocol, creating new rules to improve the system. The protocol changes are activated at a specific block number. All Ethereum clients need to upgrade, otherwise they will be stuck on an incompatible chain following the old rules.”

02/28/2019: Constantinople update, “The average block times are increasing due to the difficulty bomb (also known as the “ice age”) slowly accelerating. This EIP proposes to delay the difficulty bomb for approximately 12 months and to reduce the block rewards with the Constantinople fork, the second part of the Metropolis fork.”

1/2/2020: Muir Glacier update, “The average block times are increasing due to the difficulty bomb (also known as the “ice age”) and slowly accelerating. This EIP proposes to delay the difficulty bomb for another 4,000,000 blocks (~611 days)”

8/5/2021: EIP-1559 – London hard fork, “A transaction pricing mechanism that includes fixed-per-block network fee that is burned and dynamically expands/contracts block sizes to deal with transient congestion.”

12/8/21: Arrow Glacier Update, “The Arrow Glacier network upgrade, similarly to Muir Glacier, changes the parameters of the Ice Age/Difficulty Bomb, pushing it back several months. This has also been done in the Byzantium, Constantinople and London network upgrades. No other changes are introduced as part of Arrow Glacier.”

6/29/2022: Gray Glacier Update, “The Gray Glacier network upgrade changes the parameters of the Ice Age/Difficulty Bomb, pushing it back by 700,000 blocks, or roughly 100 days. This has also been done in the Byzantium, Constantinople, Muir Glacier, London and Arrow Glacier network upgrades. No other changes are introduced as part of Gray Glacier.”

Near-Term Market Outlook

Lastly, we previously highlighted just how leveraged and speculative the Ethereum derivatives market is right now. Reaching over 100% from its lows in June, ETH has been riding the Merge hype while acting as high beta to bitcoin (which has been high beta to equities). Traders have piled in going long into the Merge. There’s no doubt that the Merge narrative has helped to move price upwards over the last two months. But it absolutely must be noted that ETH has just been following the path of broader equities and risk.

Over the last few days, those relationships have been breaking down and ETH, along with bitcoin, are showing signs of weakness at key breakout price areas. The market looks to be at one of its most pivotal points of the cycle across a potential bear market rally conclusion, the Merge in four weeks and a September FOMC meeting in the same month.

Final Note

Our view is that with the advent of bitcoin, the Byzantine Generals’ Problem (otherwise known as the double-spend problem) found an engineering solution. With the combination of proof-of-work and a dynamic difficulty adjustment, humanity had at last figured out how to store and move value in a trustless manner across the internet. The system’s consensus mechanism is secured by a network of independent node runners, operating a software that is as simple, robust and resilient as technically possible, in order to bootstrap a new decentralized monetary system from the ground up against the interests of the world’s most powerful institutions.

We believe that ether as an asset and Ethereum as a platform are something different entirely, and many of the design/engineering decisions made by the community have led it to potentially become vulnerable to capture in the future.

From an idealist point of view, an attempt to construct a new permissionless infrastructure of financial applications using Ethereum is novel, but the rationalist in us believes that the narratives of true decentralized infrastructure and “ultra-sound” monetary properties are more of a marketing gimmick than reality.

“Governments are good at cutting off the heads of a centrally controlled networks like Napster, but pure P2P networks like Gnutella and Tor seem to be holding their own.” — Satoshi Nakamoto, November 7, 2008